I apologise in advance - this post was originally a small comment on Paul's post, then turned into a blogpost here, and a bit of a rambling one at that. Hopefully it raises some points of interest, and hopefully I can return to some of them in future posts. The area is, ironically, complex in itself.

Paul Clarke has a nice summary of systems complexity generally, and the eternal battle between getting things done, and pleasing everyone. Fortunately I haven't seen the original stories on the Christmas Tree in question, so have no idea what the context is. I prefer it like that.

I think Paul is right to highlight the role of open data as we move forwards into a technical democracy, and the possible solutions/problems coming in as a result - I think there's a good chance that transparency can lead to ever-decreasing circles of receipt-checking, process justification etc, and the whole country implodes in a swamp of exclamation marks and daily mail headlines.

These 2 questions seem rather pertinent, IMHO: "And with what discretion? Authorised by whom?" - Are these the same issues we've been grappling with for years anyway, in the form of representative democracy? On a broad picture, it's not necessary for all citizens to be involved in all decisions all of the time - so we vote for the person we think we can trust most with power. We, as voters, are handing over discretionary power so that someone else is creating a world we want to live in. I call this "trust", because even today there's no way I can know (or want to know) everything my MP is up to. I have a wife and kids and a job.

I've yet to be convinced that the drive for more transparency isn't just a way of getting us to trust politicians less. The over-riding message from on high seems to be that transparency is there to hold people to account - which I think is a real shame, as open data is far more powerful as a platform for collaboration than accusation.

Transparency as distrust leads to a bizarre situation in which people we've "trusted" via our vote are then afraid to apply that power - especially considering a vote is local, while headlines are national or global. Worse, it can drive important decisions further into obscurity and complexity to avoid such scrutiny (and here it's hard not to draw comparisons with the banking industry as a warning).

Perhaps part of the problem is believing that cost is the deciding factor in how accountable (and hence transparent) a decision-process should be. But cost says nothing of either complexity or impact - both of which are much more important in deciding the "suitability" of decisions, I would say.

Cf. two other realms - banking, as mentioned already, and open-source software.

On one hand, the uselessness of auditors in predicting the collapse of banks serves to show how bad it is to have systems that can rapidly create complex models around themselves. Compare this to how open-source software operates - for a project to be sustainable, it is vital that complexity is managed, and that the code is readable by anybody. If the code is unreadable, it grows more slowly, is more prone to bugs and security risks, and is less maintainable. Both designing and refactoring code are essential to ensure a solid output.

Can we apply these lessons to government decision-processes? If transparency is the way forwards, then I think we have to - sure, there are fundamental differences between software (which, for instance, can be forked) and a democracy (which can't, quite so easily). But as things become more open and "many eyes" start taking peeks, the productivity-gains and effectiveness of open data mean that we cna't just assume that openness is enough. Openness needs to be accompanied by feedback - the same constant re-factoring process that goes into software engineering.

In other words, it is not enough to use transparency to justify decisions already made, and to prevent bad decisions being made in future through the threat of later accountability. Openness in data needs to go hand-in-hand with an openness to change - to influence new ways of contributing, of collaborating, and of voting for those who we trust. Even new ways of thinking and feeling about why the decisions are being made in the first place.

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Thursday, November 25, 2010

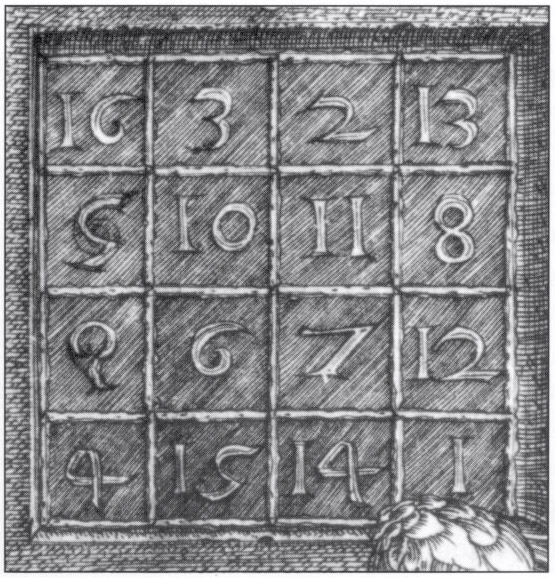

Structured data: Accessible magic?

Magic Numbers (source)

Have you ever dreamt in SQL? Few of us have, and we only ever speak of it in hushed, yet secretly astounded tones. Database development is a weird way of looking at the world. Those who venture into it too deeply may never come back to being "normal".

But at the same time, it's also like any language - reaching a state of fluidity involves a fundamental shift in thinking. To think in French is to adopt a new philosophy, and the same is true of database logic; linking and manipulating rows of data is a world away from editing each row by hand.

To explain the importance of structured data, is it important to first get across this conceptual paradigm shift? Is the ultimate draw of structured data tied inherently to a new way of seeing the world? One in which we, as data/content hackers don't see the data at all, but merely instruct a computer to do stuff with it.

Maybe this explains the "format divide" between those publishing in "closed" formats, and those publishing in open ones. If you do not know how to automate the data-munging process, then you do stuff by hand, you take a long time to do it, and you have absolutely no need for "structures" other than those in your head.

This happens everywhere, all the time: half the world lives in Excel during office hours. At some point, computers became popular as difference engines, but not necessarily good at being them. Human operators became part of the machines, rather than directors of them. In a way, this mirrored the huge factory production lines, and the endless supermarket checkouts, so most humans simply accepted this as the new way of life. Any sufficiently different technology is a form of magic. Processing as a manual task.

This happens today. Never forget that. Seeing data is more important than defining a structure for it, because structure is *hard*. Datasets have peculiarities, errors, and specifics that resist simple structuring. And changing these structures is effort - effort that involves communicating these changes to other. In short, it's easier to stick with "sloppy" data if you're not using the right tools. It's even easier if the other people using the data don't care about the tools either. Content is King.

So how do we bridge this divide between "manual data labour" and "magic"? On the up side, I believe it must happen, as data - and talk of data - becomes a public matter. Those not structuring their data will need to structure it, or face a new kind of exclusion - call it "un-APIness" perhaps.

But this doesn't help us to move into a culture of automation, of magic, which I think is important because it determines what you *believe* you can do with data. Understanding structured data is essential in coming up with new services, new applications, and new answers.

Working with people to build answers will help too. It's not enough to just want "raw data now" - to build bridges, we need to build real things based on data. We, as geeks, need to find out what people actually want. We need to show that questions can be answered with "magic", but also be open enough to demonstrate that structuring data has a direct impact on what can be done, and how quickly.

Change the tools. Rethink processes. It's time to end the conveyor-belt, factory line approach to data.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

UKGovCamp 2010 - a far-too-lengthy write-up

Yesterday was UK GovCamp 2010, a gathering of people interested in how (roughly defined) government can be taken forwards using the Internet. The day was crafted lovingly by Dave Briggs and hosted excitingly at Google HQ in London. Here's a quick rundown of where I was, what I saw, and what I'd attempt to think about the day after if I had any brain left.

Session 1 was an exercise in getting data geeks talking to data users - hypothetically, at least. The room broke into 5 or so groups, each looking at the problems that members of the public might face around certain topical issues, such as road chaos, sporting events, or sexual health. To get us thinking, we first asked what kind of information would the public want/need for each of these. In the second half, the data geeks migrated to a different group to see how data could help with answering this.

I'm not sure I came to any particular answers about either road chaos or sporting events, but did find it a useful way of breaking down the issue. Without realising it, I'd probably stumbled into the first recurring theme of my day - usability of data. Some notes of interest:

I started by taking people through what we'd done with data4nr.net in terms of UI, XML and tying it into external services like data.gov.uk. Most excellently, Richard Stirling was on hand to fill in about the latter, which probably helped to raise the issue of how we actually tie all this data together. Notes on all this below:

Finally, session 5 saw Steph Gray (slide here), Anthony Zacharzewski (links to slides) and Paul Clarke talking about persuading politicians and bureaucrats of the value of digital engagement. A great talk all round, with some inspiring, and almost crafty, thoughts being put forward about how to make websites and influence people:

OK, this post was a little longer than I thought it was, and now my stomach is rumbling. Cheers to all for a great day, and look forward to seeing the thoughts that take place in its aftermath. Keep the momentum.

Further links

Dave Briggs' write up

Sarah Lay's write up

Paul Clarke's (excellent) photo set

My own photos

Everyone's tagged photos on Flickr

Tumblr blog

Kevin Campbell-Wright's write up

Neil William's write up

David Wilcox's array of videos

Session 1 was an exercise in getting data geeks talking to data users - hypothetically, at least. The room broke into 5 or so groups, each looking at the problems that members of the public might face around certain topical issues, such as road chaos, sporting events, or sexual health. To get us thinking, we first asked what kind of information would the public want/need for each of these. In the second half, the data geeks migrated to a different group to see how data could help with answering this.

I'm not sure I came to any particular answers about either road chaos or sporting events, but did find it a useful way of breaking down the issue. Without realising it, I'd probably stumbled into the first recurring theme of my day - usability of data. Some notes of interest:

- Data may exist in a central database, but that doesn't mean everyone will be accessing it for the same reason and/or/therefore by the same means. Different groups of people have different networks - football supporters might check their club site for news, for example. Local residents might check a council site, or a paper newsletter, or even just handy signs put up on the side of the road for future travel "alerts". A good reminder why data shouldn't be tied to a particular "portal".

- It's far too easy to focus on using the latest devices to make getting data out easy. But that doesn't mean it reaches people we want it to reach. (One reason I'm so excited about Newspaper Club.)

- We draw data from many, many different places to form a decision or an opinion, e.g. form local authorities, central figures, news, private sources, etc. Linked data is probably hugely important in joining all this up, but it's also a process that we, as humans, do naturally and constantly. I think there's a big question about how we tie these two worlds together. Too big for this post though.

I started by taking people through what we'd done with data4nr.net in terms of UI, XML and tying it into external services like data.gov.uk. Most excellently, Richard Stirling was on hand to fill in about the latter, which probably helped to raise the issue of how we actually tie all this data together. Notes on all this below:

- One thing that came out of the talk around data.gov.uk is where duplicates appear (as everyone is cataloguing data, with a fair bit of overlap), but without any real way of knowing so. Unique IDs are like, really, really important, but even the definition of one is subject to interpretation problems. Simon Field noted that some users, for example, want to treat amended data as a "new" dataset, while others don't. "Unique" is subjective, perhaps. I get the impression this is going to take a while to bash out.

- Andrew Walkingshaw of Timetric (also one of the sponsors) noted two extremes of presenting data to people - "either lie to them, or freak them out". I think the extent to which either of these is necessary depends on who you're making the data public to - or, who is your audience? Different people have different training, and therefore different expectations about what the data represents. How do we manage this, or integrate it with our processes and applications?

- Maybe not everyone needs to understand data - just those in the argument? e.g. if a journalist uses some data to come to a slightly

suspectheadline-grabbing conclusion, are there people who can re-run the data and verify that? Coming out of that, do we have forums where such verifications and/or dispute can be raised legitimately? - And to return to the idea of defining metadata, there is still a question about whether definitions should be "standardised" (i.e. everyone shares the same vocabulary), or if we accept that everyone has their own "language" and the challenge is to map between these somehow. If the former, is it practical to define one in advance, or just let people make their own, in a more organic nature?

I think there was lunch at this point.

Session 3 was on Using Wordpress in Government, run by Simon Dickson of Puffbox. I've been doing a fair bit of integrating PHP sites with Wordpress this year, so was interested in hearing about what other people had done with it, and how. A lot of the session seemed to be extolling the power of Wordpress rather than focus on the grittier details of rolling it into a project, process or workplace, but it was interesting to hear where it's being used, and a great chance to finally meet Steph Gray in person.- Good to note that about half of all (central?) government departments are "dipping their toes" into Wordpress, although perhaps under the second theme of the day - covert innovation which I'll pick up at the end.

- Good point from Simon - that for all the talk about re-using software, making sites, etc, "Wordpress has done it - we are doing it." Good tools make exploration easy, and make it easier to experiment with little nuggets of progress without too much risk/cost/project management. We have good tools already that mostly just need tweaking, why not use them?

- Wordpress is great for swapping content between sites, as everything is available as RSS feeds. I suspect this ties into my session on finding and filtering data more than I realise.

Finally, session 5 saw Steph Gray (slide here), Anthony Zacharzewski (links to slides) and Paul Clarke talking about persuading politicians and bureaucrats of the value of digital engagement. A great talk all round, with some inspiring, and almost crafty, thoughts being put forward about how to make websites and influence people:

- Talk about activities, not tools. Talk about how what you want to do results in outcomes. Decision makers like to see a direct link between what you propose and what gets saved.

- Use narratives, storytelling. But be careful about who you include in your stories - different viewpoints and people are perceived in different ways. Sometimes people love the idea of appealing to the "main in the street". Other times the same man is seen as, say, unreliable or anecdotal.

- Terms and words are political, as I've noted before. Use terms, especially "buzzwords" carefully, as they may "belong" to particular groups. Technical speak suffers from the same problem, I'd say. WTF do AJAX, Web2.0 and WTF mean anyway?

Themes

The two recurring threads I really picked up on during the day were:- Usability of Data - How can we make data as a whole easier for everyone to find? How do we know what data is out there, what it means, and what it can/can't be used for? How can we access it other than clever websites?

- Covert Innovation - A lot of the exciting stuff in government is being done "under the radar". This, in itself, is not necessarily a problem, but there were a couple of tales around the idea that successful efforts would be prevented if they were made more public - for various reasons. I think currently there are a lot of conversations going on, but within almost hushed tones - tones which can only get loud once this success has reached critical mass and gone "mainstream" to the point where it can't be covered up any more. The tales of Gordon Brown giving Tim Berners-Lee free reign were great, but really not enough. Hiring a hugely respected scientist is quite different to trusting your own staff.

Failure is an option, even necessary, but a lot of the time organisations believe that it isn't - perhaps because they're used to thinking in terms of large scale projects (= large scale failure)? Contrariwise, a lot of the efforts seen at GovCamp were small scale innovation which can and even should fail quickly and easily (e.g. "does this Wordpress plugin do what we want?" Click. Install. "No." Learn. Move on.) The move towards opening up data is all about risk management. Bang the rocks together.

OK, this post was a little longer than I thought it was, and now my stomach is rumbling. Cheers to all for a great day, and look forward to seeing the thoughts that take place in its aftermath. Keep the momentum.

Further links

Dave Briggs' write upSarah Lay's write up

Paul Clarke's (excellent) photo set

My own photos

Everyone's tagged photos on Flickr

Tumblr blog

Kevin Campbell-Wright's write up

Neil William's write up

David Wilcox's array of videos

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)